The artist Richard Prince, who is sometimes known as the #PrinceofAppropriation, claims that copyright law protects the artistic style he calls “appropriation art.” Photographer Donald Graham filed suit against Prince, alleging Prince infringed the copyright in Graham’s photograph, “Rastafarian Smoking a Joint,” when Price used it for his own work. In his initial defense, Prince has embraced, rather than shunned, the “appropriation” label.

Prince is a one of the leading names in art. Several of his works have sold for amounts in excess of $2 million. The “wealthy and the famous,” including Jay-Z, Robert DeNiro, and Brad Pitt attend his exhibitions and collect his works.

A prior case, Cariou v. Prince, led to a new fair use precedent. In that case several of Prince’s works based on Cariou’s original photos were found to qualify as fair use, including Prince’s work, “Graduation,” based on the Cariou photograph “Yes Rasta.” Prince is now trying to move that precedent a step farther.

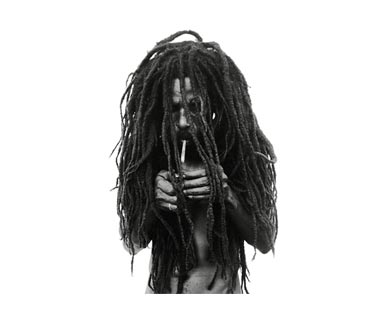

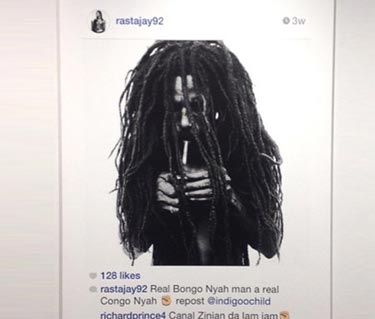

Like Cariou before him, Graham claims that Prince’s appropriation art infringes his copyright. The case involves Graham’s 1997 photograph, “Rastafarian Smoking a Joint, Jamaica.” Prince’s allegedly infringing work used Graham’s copyrighted photograph, taken from a post by an Instagram user, rastajay92. Prince cropped the Graham photograph slightly, included the surrounding Instagram interface, and added his own “comment” at the bottom of the work (mimicking Instagram commentators).

After Graham became aware of Prince’s use of his photograph, Graham posted his original photograph on his own Instagram account, along with the notation: “How to credit a work: ‘Rastafarian Smoking a Joint’ © 1997 Donald Graham.”

| “Rastafarian Smoking a Joint, Jamaica” and Prince's Instagram-inspired work |

Prince responded to Graham’s copyright infringement suit with a motion to dismiss, arguing fair use. In his motion, Prince claims that it is fair for one artist to use the work of another. He references other artists, ranging from Andy Warhol to Pablo Picasso, who could be considered appropriation artists. For example, his motion reproduces Warhol’s work, “Gold Marilyn Monroe,” which, according to Prince’s motion, uses “an iconic photograph of Marilyn Monroe silkscreened onto a gold background.” (The “iconic image” is a publicity still from the 1953 film “Niagra.”)

Prince acknowledges that he used Graham’s photograph without Graham’s permission. His motion focuses on his argument that his work qualifies for the fair use defense. Because “transformative use” is central to a fair use analysis, Prince claims that he “transformed” the original photograph by enlarging the screenshot, preserving the Instagram visuals and texts, and adding his own username and comments. Prince claims that a reasonable observer would recognize that Prince’s artwork adds “new expression, meaning, or message” to Graham’s photograph.

In claiming his work is “transformative,” Prince argues that the aesthetic differences in his work convey new expression and meaning that is sharply different from that conveyed by Graham’s photograph. He claims that while Graham’s photograph “captures the spirit and gravitas of the Rastafarian people,” his work comments on the power of social media to broadly disseminate others’ work and people’s need to receive “likes” and “comments.” Prince argues that the Graham photograph was merely “fodder” for his artistic commentary.

In response, Graham asserts that the Court should confine its analysis to those additions actually authored by Prince — the text line “Canal Zinian dam lam jam” alongside an emoji. Graham claims that if Prince’s kind of copying of photos became widespread, the market for photographs like Graham would be “usurped.” He argued that a purchaser could then escape customary licensing fees by merely uploading the original work to Instagram, or some other social media source, and subsequently making a print in the same size and quality as the original.

Mike Nepple is a partner in Thompson Coburn’s intellectual property group. He can be reached at (314) 552-6149 or mnepple@thompsoncoburn.com. Justin Mulligan is an associate in Thompson Coburn’s Intellectual Property group. He can be reached at (314) 552-6227 or jmulligan@thompsoncoburn.com.