Home > Insights > Publications > Correcting Patent Inventorship: The High Bar to Overcome Being Trimmed Fat

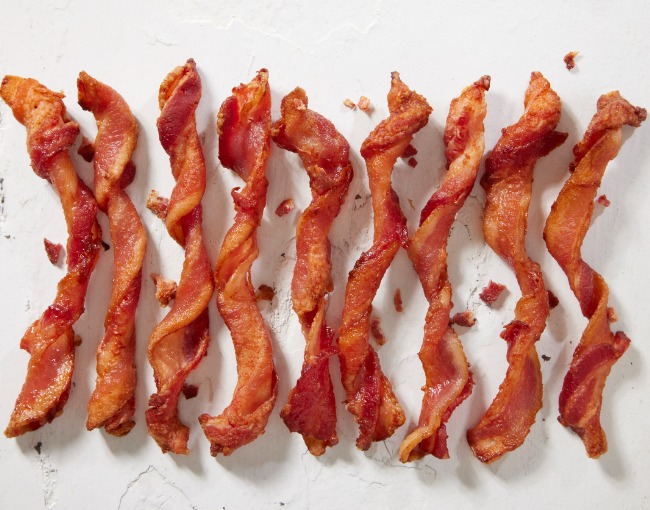

How do you take a case about patent inventorship and make it better? Add bacon. The Federal Circuit’s recent decision in HIP, Inc. v. Hormel Food Corp., 66 F.4th 1346 (Fed. Cir. 2023) illustrates the high bar that must be met to convince the courts to add a person as a joint inventor to an issued patent.

In the 2000’s, Hormel, a company that sells bacon, and HIP (formerly Unitherm Food Systems, Inc.) collaborated on ways to make tastier bacon. In 2018, Hormel obtained US Patent No. 9,980,498 (“the ’498 patent”), claiming a method of making precooked bacon. The method involves a two-step process in which bacon is first preheated to melt the fat and form a protective layer that prevents water condensation from diluting the tastiness during the second cooking step. Four inventors were listed on the ’498 patent and all assigned their interest in the patent to Hormel.

In April 2021, HIP filed suit in the United States District Court for the District of Delaware, alleging that David Howard of HIP was either the sole inventor or a joint inventor of the ’498 patent. Howard claimed that he disclosed certain aspects of the claimed invention during his time collaborating with Hormel. The district court determined that while Howard was not the sole inventor, he was a joint inventor based solely on his contribution of the concept of infrared preheating, which was an alternative preheating embodiment listed in dependent claim 5 (e.g., a microwave oven, an infrared oven, and hot air). The district court instructed the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) to add Howard as a joint inventor which would make HIP a joint owner of the ’498 patent with Hormel.

Hormel appealed to the Federal Circuit, raising two issues. First, that Howard’s alleged contribution of preheating with an infrared oven was well known and part of the state of the art and that it was not significant when measured against the scope of the full invention and second, that Howard’s testimony was insufficiently corroborated.

The Federal Circuit’s analysis begins by discussing the presumption that inventorship in an issued patent is correct, therefore, the standard to add an inventor post-issuance is high:

The burden of proving that an individual should have been added as an inventor to an issued patent is a “heavy one,” Pannu v. Iolab Corp., 155 F.3d 1344, 1349 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (quoting Garrett Corp. v. United States, 422 F.2d 874, 880 (Ct. Cl. 1970)), and “the issuance of a patent creates a presumption that the named inventors are the true and only inventors,” Gen. Elec. Co., 750 F.3d at 1329. Thus, an alleged joint inventor must prove a claim of joint inventorship by “clear and convincing evidence.” Hess v. Advanced Cardiovascular Sys., Inc., 106 F.3d 976, 980 (Fed. Cir. 1997).

Hip, Inc., 66 F.4th at 1350. To qualify as a joint inventor, a person must make a significant contribution to the invention as claimed. Id. (citing Fina Oil & Chem. Co. v. Ewen, 123 F. 3d 1466, 1473 (Fed. Cir. 1997). The significance of a person’s contribution is determined by using the three-part test articulated in Pannu, a joint inventor must: (1) contribute in some significant manner to the conception of the invention; (2) make a contribution to the claimed invention that is not insignificant in quality, when that contribution is measured against the dimension of the full invention, and (3) do more than merely explain to the real inventors well-known concepts and/or the current state of the art. Pannu, 155 F.3d at 1351.

Hormel argued that the district court erred in holding that Howard was a joint inventor because at the time of his disclosure, the concept of preheating with an infrared oven was well known and part of the state of the art. Hormel alleged that the district court failed to properly consider a prior printed publication, U.S. Patent App. Pub. 2004/0131738 (“Holm”), which taught using an infrared oven to preheat meat pieces three years before Howard’s and Hormel’s collaboration. Hormel also argued that the district court failed to analyze the significance of Howard’s alleged contribution in light of the full invention and that the district court erred in its conclusion that infrared preheating was significant, for example stating that there was no indication that infrared preheating solved any specific problem in the field of the ’498 patent.

HIP responded by arguing that Holm was an obscure publication that was never commercialized or described in a marketing or sales brochure or in a textbook. HIP argued that infrared preheating of meat does not become current state of the art merely because it was mentioned in a single patent publication. HIP also argued that the district court did not err in holding that infrared preheating was a significant contribution.

A three judge panel of the Federal Circuit reversed. The court agreed with Hormel that under the second Pannu factor, Howard’s alleged contribution of infrared preheating was “insignificant in quality” to the claimed invention. The court noted that preheating with an infrared oven was only mentioned once in the entire ’498 patent specification, as an alternative to microwave preheating, and only as an alternative embodiment in a single dependent claim. In contrast, the court found that “preheating with microwave ovens, and microwaves themselves, featured prominently throughout the specification, claims, and figures.” Hip, Inc., 66 F.4th at 1351. Further, while the examples described multiple different methods to preheat bacon slices, strikingly, not a single method of preheating in the examples used an infrared oven. The court additionally emphasized the “centrality of the microwave oven, and the corresponding insignificance of the infrared oven, to the current invention.” Id. at 1352. Because the court held that Howard’s alleged contribution was “insignificant in quality” when “measured against the dimensions of the full invention”, the court concluded that Howard was not a joint inventor of the ’498 patent. Id. at 1352-53 (citing Pannu, 155 F.3d at 1351).

The court declined to comment on whether Howard contributed in some significant manner to the conception of the invention or did more than merely explain to the real inventors well-known concepts and/or the current state of the art (i.e., the first and third Pannu factors, respectively), stating that failing to meet just one factor is dispositive on the question of inventorship. The court also did not reach the question of corroboration for Howard’s testimony.

Convincing a court to add an inventor to an issued patent is no easy feat. According to the Federal Circuit, all three Pannu factors must be met. What makes a contribution significant against the dimension of the whole of the invention is not an objective test. The more mention, however, of an inventor’s contribution in the discussion, examples, figures, and/or claims of an application, the better the chances of persuading a court that this factor weighs in favor of the inventor to be added. The more related the contribution is to the actual point of novelty of the invention and the greater the evidence of a lack of common knowledge of the contribution in the prior art, the stronger the case for joint inventorship will be. A lack of evidence of such contributions may leave your bacon cooked.

Wil Holtz and Sylvia Wilson are members of Thompson Coburn’s Intellectual Property practice group.